17 Mar What is modern art – good for?

A kind of art- and exhibition practice based on anonymity and copying has spread over the European continent since the early-mid 1990s, with an outpost in New York. The presentations not only have always been accompanied with related (art) historical and theoretical ruminations but they were often consciously scheduled to coincide with major events of the international art world for reasons other than just a shifty strategy to maximalize attention. The International Exhibition of Modern Art, a curious re-production of the 1913 Armory Show for instance, was on view in the Pavilion of Serbia and Montenegro at the 2003 Venice Biennale.

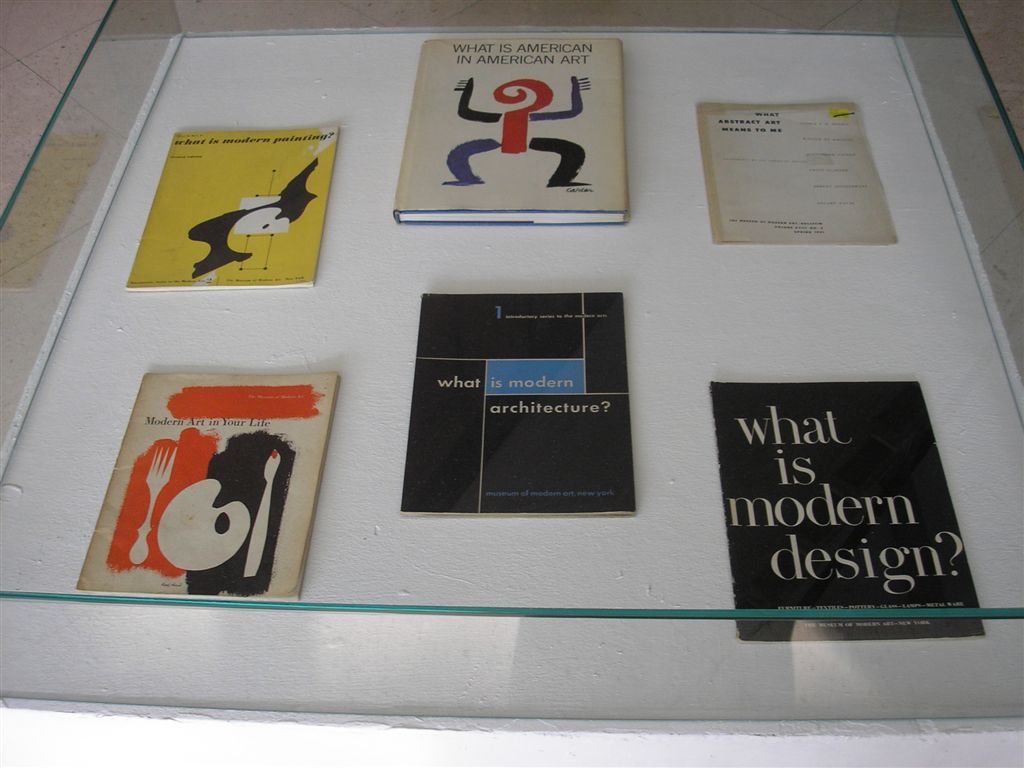

In 2007, Documenta 2 (1959) was similarly re-produced, and arguably re-purposed, at Kunsthaus Dresden just when the arts community was flocking to Kassel, some 350 km further west, to see „real” Documenta 12. A number of permanent nods existed and continue to exist as well: the former Salon de Fleurus in New York (1992–2014), the Kunsthistorisches Mausoleum (since 2002) and the Museum of American Art (MoAA) in Belgrade and Berlin, as well as occasionally Galerie 35 (Berlin, now closed). These permanent venues and temporary presences have earned the attention of Künstlerhaus Bethanien: in October 2006, it housed the group show What is Modern Art?, compiling the various projects. As you may guess, the exhibition in Bethanien ran parallel with the Art Forum, Berlin’s International Fair for Contemporary Art.

The Museum of American Art in Belgrade did not exactly exist as a physical space at the time of its first, and until today only, intervention in the Winter season of 2006-07. As an “educational institution dedicated to assembling, preserving and exhibiting memories on American modern art shown in Europe in mid-20th century” (press release), MoAA nevertheless brought (back) two exhibitions, Modern Art in the USA and Vanguard American Painting to Belgrade and Zagreb. Both exhibitions traveled Europe in 1956 and 1961-62, respectively, but in the East Bloc, it was only the cities of Yugoslavia where these selections of modern American art could be seen, thanks to the cultural openness of Yugoslavia toward Western countries.

The above-listed ventures all revolve around such dilemmas as authorship, the construction of (art) historical narratives, object making vs. conceptual art – and there is always a number of subtexts that expand the scope of reflection on the occasion of each manifestation. In Belgrade and Zagreb, these included the nature of US–Yugoslav relations which profoundly altered since mid-century and most eminently, through the 1999 NATO-bombing of (the Federal Republic of) Yugoslavia in the wake of the Kosovo conflict. More broadly, the obstinate foregrounding of modern American art serves to tease out a praiseworthy aspect of New York’s “stealing the idea of modern art” in the post-World War II years. This “theft” took place at a time when the appreciation of cultural products was still largely based on nationally compartmentalized perceptions, as the anonymous author of these displays underlines. The Venice Biennale is of course a prime example of the anachronistic idea of national representation, hence the anonymous “former” artists’ act of high-jacking, for an International Exhibition of Modern Art of the pavilion that Serbia and Montenegro inherited from a dissolved Yugoslavia.

In contrast, American abstraction had introduced a sort of international “art identity”, which was of extreme importance after the second World War—and was made the underlying organizing principle of documenta 2. By a similar token, consciously blurring national identities might have been equally important for the successor states of Yugoslavia in the early 21st century, where MoAA brought back postwar American modern art.

MoAA’s remembering exhibitions follow a uniform method: the artworks once registered in the original exhibition catalogues are (re-)painted, clearly lacking an intention to create misleadingly exact replicas as far as materiality, brushwork, or size is concerned. (Occasionally, media reports featuring the art exhibits together with random visitors are also “re”-painted and exhibited as part of the museum “collection”). Among other things, this irreverent conflation is a playful yet earnest engagement with the inequality of access to cultural goods in centers and peripheries and in periods before mass tourism. Admiring randomly sized, often black-and-white reproductions in better or poorly printed publications was the essential way in which art lovers behind the Iron Curtain encountered, or visitors to the Kunsthistorisches Mausolem encounter, their Duchamp, Stella, or Mondrian: grand monuments of art history reduced to signs.

No Comments