14 Apr No Psychedelic Lore – Mushrooms and Bubbles at the Smart

In the midst of my search for a PhD position, itself a transnational quest taking me from Berlin to the Midwest, I had the opportunity to visit the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago. The date was February 23, 2023, coincidentally the opening day of not all realisms: photography, Africa, and the long 1960s, an archival exhibition curated by photography specialist and UChicago alum Leslie Wilson. Considering how I, a Californian living abroad, routinely look at Africa from afar, currently from my perch in a European capital, but potentially soon from a major American city, I was curious to find out how this sense of distance would be explicitly thematized in the exhibition itself. What role, that is, did photography play in triangulating Africa, Europe, and the United States during decolonization, the cold war and apartheid, some of the principal conflicts of that very long decade? Moving closer to the exhibition’s various prints, photocollages, photobooks, newspaper articles, and other documents, I gravitated towards the examples in which I could sense multi-continental forces at play, images that invoked a global political theater.

After stepping through an oversized patch of retro-colored houndstooth, a vibrant digital print of the textile applied directly to the glass entryway of the exhibition, I first encountered the smile of a young girl, who was, despite the figurative emphasis of the exhibition overall, the only person in this montage of 1960s maps.

She personifies the independence and formation of the Mali Federation, a short-lived, utopian juncture of present-day Mali and Senegal. Together with other collaged elements, which might have been excerpted from touristic postcards, her head encircles a contour drawing of the country. Heritage sites in the east, such as the iconic mud-brick Mosque of Bamako and Gouina Falls, spanning over 500 meters, unite with modern wonders in the west, such as a multi-storied administrative building, Dakar’s skyline, and a remarkable architectural novelty of the city, Wallace Neff’s bubble houses. The girl expresses not only gay enthusiasm for the flow of the heartlands into the metropolis, tradition into invention, but an openness to American partnership. The quickly built and aesthetically upbeat bubble houses, which departed from the Hollywood villas upon which Neff had built his fame, were inexpensive and responsive to the region’s hot, windy, and sandy climate. Here was an economical solution to the region’s housing shortage and an opportunity for Neff to reinvent himself as a builder of the people. Whether or not one repudiates this as a neocolonial transaction today, the collage documents the foregone hope for first world and third world actors to collaboratively resolve the young state’s issues, while lending it midcentury flare.

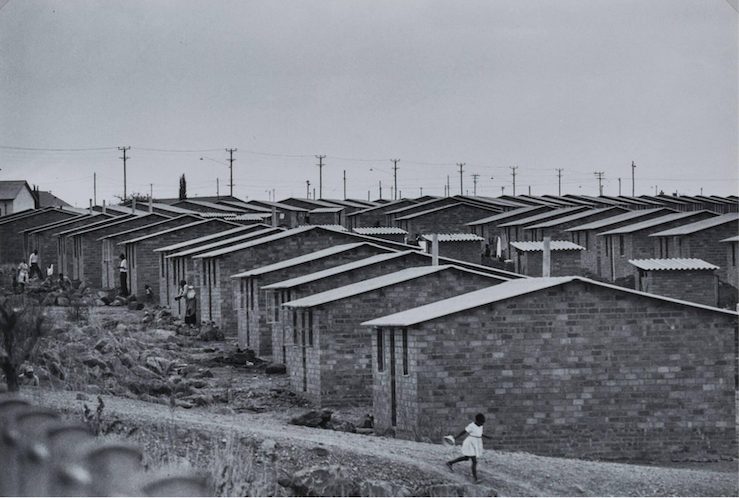

Against such optimistic representations of decolonization, materials from South Africa steer the visitor into foreboding and outright grim territory. The curators prominently arranged Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage (1967), a photography book revealing injustices of apartheid, on a display island in the exhibition’s main room. While individual plates are vertically oriented and individually framed, copies of the book, opened to the respective photographs, are laid out horizontally below. This clever L-shape entails a hinge between two different guises of the images: as individual, free-standing artworks and as illustrations in politically motivated texts. As artworks, Cole’s striking compositions are given space to resound, to the full extent of their formal intensity, and as books, manipulable objects of education, the importance of their transnational peripatetic lives comes into view. In one print, a lone girl is engulfed by the inhospitable architecture of a newly developed township. The page below describes how the situation is even more dire for those who have been forced into impermanent tents, rather than solid brick structures.

Taken in secrecy and without government permission, smuggled out of South Africa, and compiled into a book by Random House (printed in New York and then London), the shots first allowed Europe and America to peer into the displacement, infrastructural marginalization, and deplorable bodily subjection of the Black population in South Africa. The stark imagery helped precipitate international condemnation of apartheid.

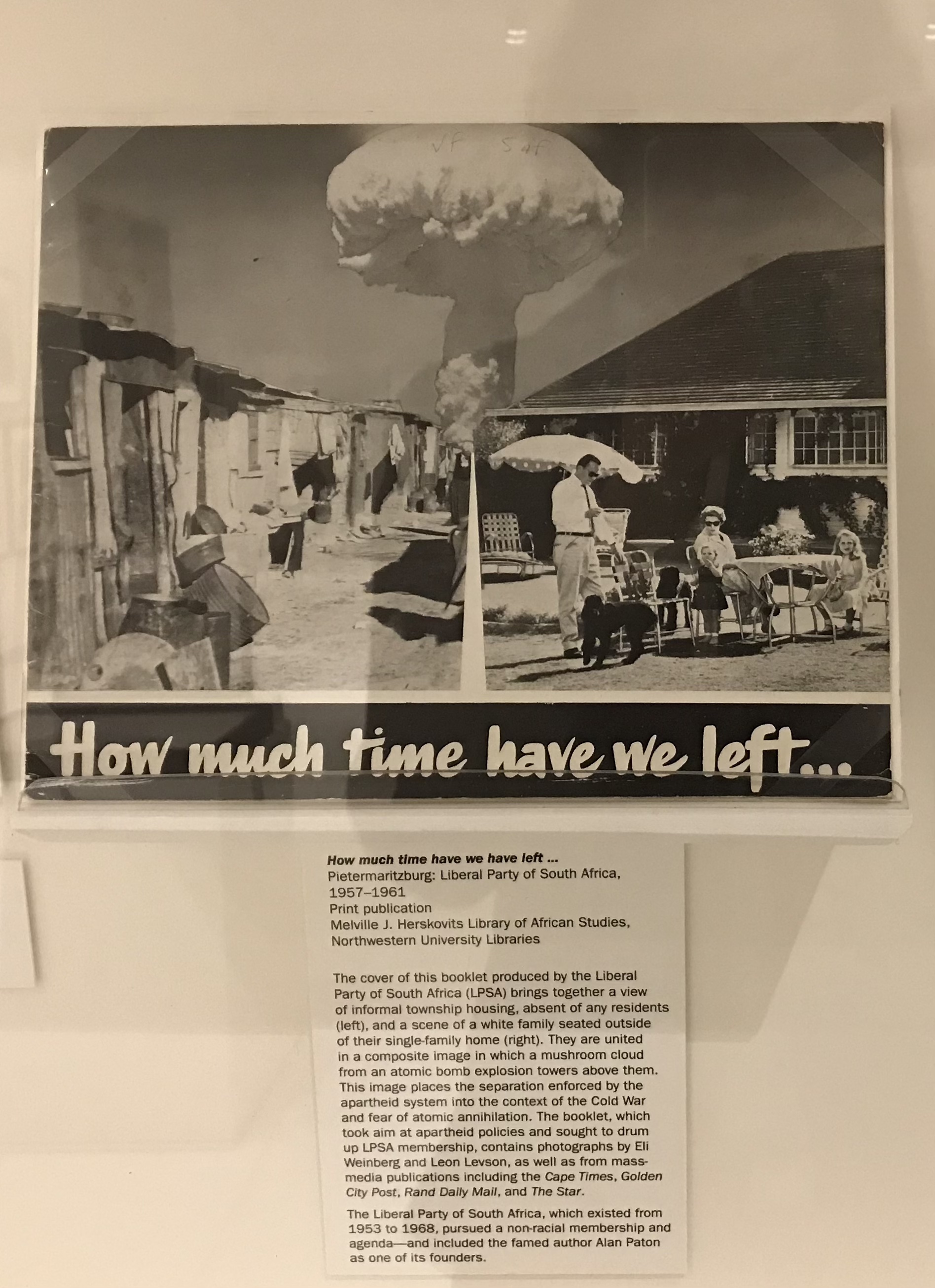

A billowing mushroom cloud in a collage on the cover of a neighboring booklet, printed by the non-racial Liberal Party of South Africa, thrusts the housing crisis into the atmosphere, where it can be seen from afar and recognized as a global threat.

Tension in the image is built by contrasting architecture and urban planning: on the left, laundry and washing basins clutter the alleyway outside a row of patchwork shacks; on the right, a white family, complete with poodle, enjoy a luncheon on the lawn outside their cottage-like home. Emerging from the seam between the two domestic settings, the cloud mobilizes cold war fear of nuclear catastrophe to combat such inequitable living standards. A museum label below informs us that the booklet also included photographs by Eli Weinberg, a Jew from Latvia, who, after his exile to South Africa before WWII, became a portraitist of Nelson Mandela and an underground Communist organizer. Set within this transnational context, the collage not only attributes something sinister to the 1950s suburban nuclear family, whose affluence often depends on expropriation, but also makes clear that the universal fight against capitalism cannot be won without stopping such oppression.

How the show managed to strike an optimistic note about the end of colonialism and African statecraft, while also speaking to the deep horrors of racism and inequity – indeed, holding those two movements in tension, rather than one absorbing the other – seemed, to me, to resonate with the challenges of the University and Chicago itself, a famously segregated city.

Not all realisms. Photography, Africa and the Long 1960s, February 23 – June 4, 2023, Smart Museum of Art.

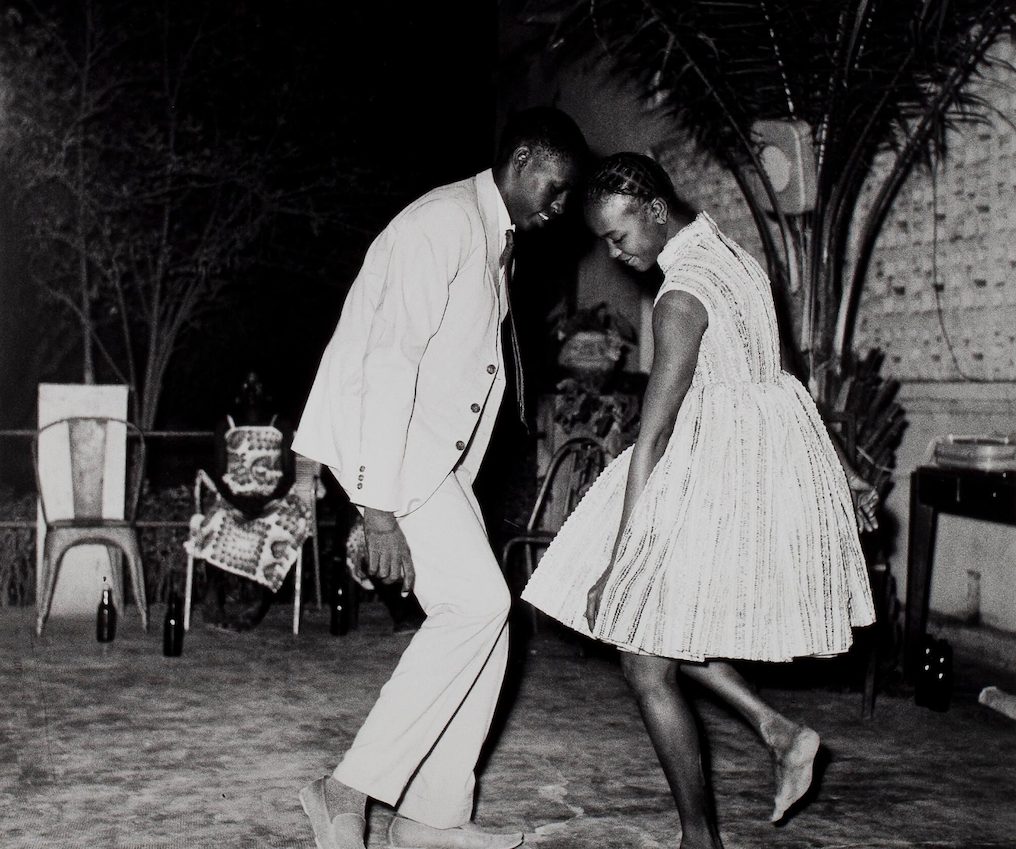

Featured image: Malick Sidibé – Nuit de Noël (Happy Club), 1963

No Comments