16 Dec Finding Connections in the not so Lonely City

Two days after the second Linking Art Worlds seminar ended in Budapest, my hometown, I was headed to the airport to embark on a journey to New York City. I was about to spend one month there to conduct research connected to my PhD project and explore the art scene. With Olivia Laing’s book, The Lonely City in my backpack, I was ready to go. I discovered the work of Laing through reading the autobiographical book entitled Close to the Knives by American artist David Wojnarowicz who died of AIDS in 1992. The introduction of this volume was written by Laing, and when I saw the cover of her aforementioned book, I could relate to its subtitle: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone. Through the art of various artists living in or inspired by New York City, such as Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol or David Wojnaworicz, Laing investigates what it means to be alone. Reading this book made me realize that although I was practically alone in New York City, I did not feel lonely. I rather felt that I’m making connections, not just with people, but with the themes of our seminars as well. I will highlight some of my transatlantic cultural encounters through exhibitions I visited.

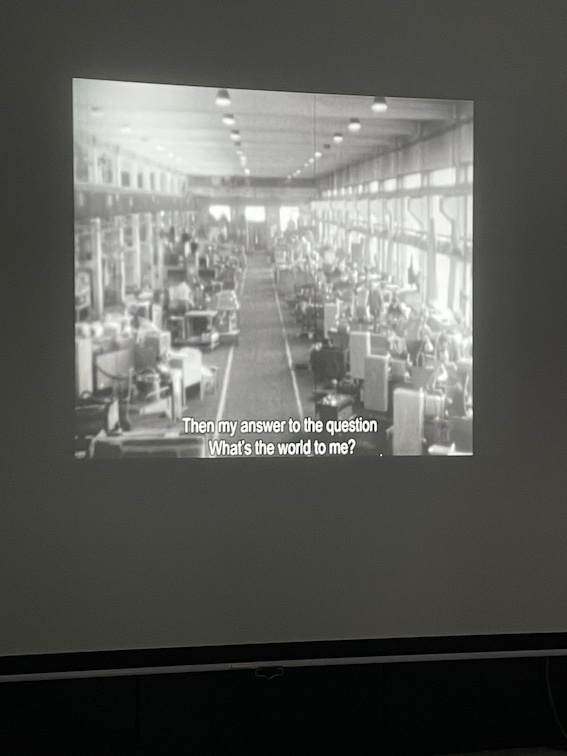

With a beautiful view on the Manhattan Bridge and the Lower East Side, the gallery and studio on Canal Street offers an affordable solution for artists to work and exhibit in downtown New York. This Chinatown space operated by Marco Bene, was so new it did not even have a name when I was there. The pop-up show curated by Bene featured works of Hungarian neo-avant-garde artists from the 1970s such as Gábor Bódy, Miklós Erdély, Katalin Ladik, Dóra Maurer, Tamás St.Auby and Endre Tóth. The exhibition, only open for a week, was showcasing the research of Bene, whose father was Hungarian and maintained friendly relationships with some of the artists exhibited. Growing up in Spain, studying in London and now living in New York, Bene wanted to make an homage to his late father and his special relation to Hungarian art. Visitors could watch Tamás St.Auby’s film Centaur, showing found footage scenes from Hungarian citizens’ daily life with a voice over about existential questions. These imaginary dialogues revolving around work, money and power using the rhetoric of socialist propaganda add a philosophical and critical layer to the film. Because of its political content the movie could not make it to a public screening, and the only existing copy of it was restored for the Istanbul Biennial in 2009.

A work by poet, actress and performance artist Katalin Ladik was also on display. In this series of photos Ladik presses her face to a glass sheet as an act of dividing herself from the audience but also of deforming a part of her body. The same gesture appears in Ana Mendieta’s 1972 work, Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints). This common visual motif capturing the vulnerability and exposure of the female body connects the work of two women artists living and working in different continents and cultural scenes.

Among the documents there were photos from the family archive capturing Bene’s father hanging out with St.Auby. Bene also interviewed Hungarian art historians such as Emese Kürti or Katalin Székely as an initial step in mapping his father’s network in the 1970s Budapest art scene. I knew most of the works pretty well as with the international discovery of this era of Hungarian art they became emblematic pieces in the last decade. It was indeed a little strange to see these artworks in such an environment. Talking to the curator about his personal motivation and desire to find his own cultural roots got me pondering about my relation to these works, mostly created by men.

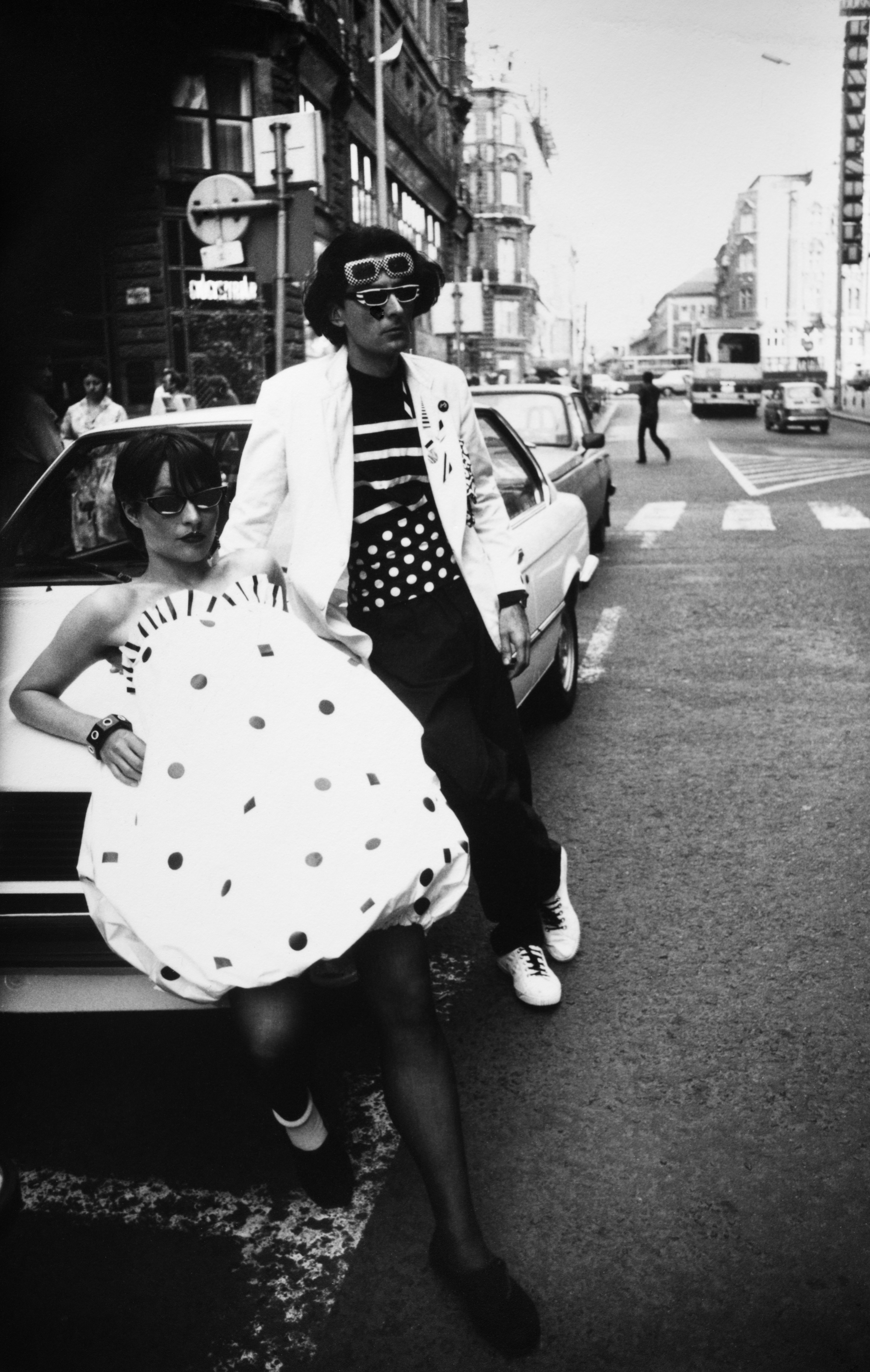

After the conceptualism of 1970s art I was exposed to the queer maximalism of Matthew Flower (b. 1972), a provocative artist better known as Machine Dazzle. The first solo exhibition was dedicated to the artist’s costumes designed for theater, street performances, photography, video and music. Excessive in color, form and a variety of materials, Machine Dazzle created costumes and sets for drag shows in the art scene of 1990s New York. His dresses are more like sculptures that extend the body of the performers, which was also typical in the work of Hungarian avant-garde fashion designer, Tamás Király (1952-2013).

Mixing fashion with the elements of theater and fine art, Király emerged in the underground art scene of Budapest in the 1980s. Using obscure materials including tar paper, golden cables, dolls, plastic bags filled with liquids, biscuits or even gelatine, Király realized a queer vision behind the Iron Curtain. Unlike Machine Dazzle, whose excess had almost no limit, Király built his creations with DIY methods, often out of cheap materials. Despite his limited possibilities Király staged grandiose fashion shows in the 1980s in Amsterdam, Berlin and New York. In Budapest he usually worked with models he picked up on the streets. These unusual characters, such as plump ladies, feminine men or bodybuilders paraded on the catwalk in Király’s extraordinary creations. Walking along Machine Dazzle’s costumes embracing maximalism, I wondered how these pieces supported queer artists in expressing and inventing themselves. Coming from minority communities, the performers Machine Dazzle collaborated with could thrive in kitsch and camp, creating a parallel, much more exciting reality. Király’s pieces challenging the social norms, the notion of human body and sexuality had impact beyond the catwalk. From time to time his fantasy world emerged in the streets of Budapest: his fashion walks were peaceful demonstrations against the dullness of ready-made clothes. Király’s playful and extravagant fashion was very much in contrast with what was available in stores or what the majority of people expressed through looks or style. His maximalism also had a community forming effect: his downtown Budapest punk boutique, operated together with Gizella Koppány and Nóra Kováts, quickly became a meeting point for underground musicians and like-minded people looking for an attire out of the ordinary.

No Comments